We were an early-stage startup, made up of three founders who’d spent a sum total of more than two decades in silicon valley. We dedicated a large part of our careers to the tech industry, from startups to big-tech, and armed with these experiences, we thought we made an elite team. On paper, admittedly, we looked special. “We don’t obsess over product above customers, that’s a trap other startups fall into.” “Competition!? That doesn’t bother us.” “Build, test, repeat. Build, test, repeat…We know the formula for PMF!”. Other startups fall prey to common pitfalls, but not us … fate, it turns out, is not without a sense of irony. We fell victim to one of the leading causes of death for nascent companies: Co-founder break-up. Our journey started with us coalescing around our CEO’s passion for journalism and startups, and that gave the company its early momentum. We traversed quickly through the ideation phase to shipping a product, but when we joined YC, the trajectory of the company went sideways. It shifted towards doom. Our acceptance into YC came with a condition: Abandon the news industry and chase something more lucrative, which leveraged our experience as a competitive advantage (we had no professional credentials or hands-on experience working in a media company). At the time, I knew it was a pivotal decision but I didn’t realize that we signed the company’s death warrant. In hindsight, it was simultaneously the worst decision for the company, but the best decision I’ve ever made.

Background

The chronology of events:

- My two co-founders (lets call them Blake and Nick) met through mutual friends in 2017, and developed a solid friendship over the years.

- Nick and I met at Google near the end of 2021, over our mutual interest in crypto, and worked together on a number of related projects.

- Early 2023, Nick and I enjoyed a series of conversations about joining forces to launch a company together. There was some jockeying for the CEO position, a discussion about division of responsibilities, shared goals and values, etc. and ultimately we came to a mutual understanding.

- Around the same time, I became acquainted with Blake.

- We decided to team up on March 1st of 2023. All three of us became full-time on April 5. Nick was the CEO, I was the CTO, and Blake was the CPO.

- At the time, I was agnostic about the target market, believing that a team composed of A-players can win anywhere. For Nick and Blake, the mission was pre-selected: The company would serve the news industry.

- So we started interviewing many journalists and news practitioners. After cycling through some ideas that didn’t really show promise, we landed on this vision to build news intelligence services. The idea was to serve data (claims, quotes, sources, etc.) and derived insights (eg. topic clustering) extracted from news and news-adjacent content (eg. legislation), so that customers don’t have to build and maintain costly data and analysis infrastructure. At this moment, Factored Media was born (we incorporated mid-April).

- We also shipped our first product: It extracting structured data out of recordings of government meetings (eg. House subcommittee meetings, municipal zoning board meetings), as journalists we’d come across spent a ton of time listening to these.

- We applied to YC on the back of this vision and product. Even though our live product observed minimal traction and 0 paying customers.

- Mid-May, we got an interview. I was stunned when the Zoom window expanded to show a prominent YC partner (someone who I admired from afar). They started the interview with the remark, “your idea scares me”, then gave us two options: Either we could convince the partners on the call that the market we had in mind was big (by VC standards) or we could pitch them other ideas. Still starstruck and momentarily paralyzed by the question (all of our interview prep was obsolete at that point), we … kind of did both. I have difficulty recalling the ensuing exchanges (my mind has blocked the traumatic memories), but when the meeting ended after what felt like an eternity, we were pretty sure we were not going to be joining the upcoming batch.

- After a day spent in malaise, just as Nick and Blake were leaving the office, we got a late evening email from one of our interviewers asking if we could meet the following morning.

- We used the following morning to game out different scenarios: Will they accept us despite failing to make a case that our product had the potential to sprout into a venture-scale business? Or will they ask to pitch a different idea? Or will they give us a blank cheque? As we contemplated each of the parallel universes, we asked each other what we wanted to do faced with each scenario. I’ve always been flexible about the market we choose so my preference was to join YC over continuing with the current path. Blake shared that preference. Nick was on the fence. But Nick believed in the team, a belief I also had internalized, and was willing to join YC even if it meant forfeiting the progress we had made.

- In the second interview, we witnessed the YC partner’s friendlier side. The bottom line was simple: if we wanted to join YC, we had to abandon what we were doing and do something else (“literally anything else” were their exact words). And the partners would offer us the space and time to find that new direction. We unanimously chose to accept the deal in the interview.

- I admit, I experienced a high for a few days after, feeling the psychological rewards of achievement and status. That didn’t last very long. This was a turning point for the company. We spent the next few months in agony, pinballing from idea to idea, sector to sector — unable to find our footing in a space/idea where we all had conviction. We blitzed through enterprise search, developer environments-aaS, federated learning – These are just some examples. I was willing to tolerate the tumult because I harbored the belief that as long as we stuck together, our perseverance would pay-off. But then August rolled around, which marked the beginning of the end.

- Early August, Nick told the team that things weren’t working, and we needed to make some changes. His heart was stuck in journalism and he couldn’t see continuing with the team given his lack of alignment. He wanted to return to our pre-YC path, the one we had to give up in order to join the program. At this time, he predicted the most likely outcome was that he would end up stepping away, but was willing to give it one more shot with someone else leading the charge. Although he hedged his feelings, I’m pretty sure he knew, deep down, his true intention was to leave the team, but in order to save face and his reputation, he would complete the batch.

- I was in denial at first. I tried to figure out a way I could re-inspire Nick and keep him committed to the team. As we threw ourselves back into the crucible of ideation, there were a series of altercations between Blake and I that opened my eyes. I realized we had disagreements on how to shepherd the company and our thinking styles clashed. This happened over a period of days, where I also passed through all the stages of grief, and on the other side, I accepted that Nick was a lost cause. But I also came to the conclusion that in Nick’s absence, Blake and I couldn’t make it work. (It’s astonishing how much you can truly learn about a person from the way they argue.)

- As a team, we reluctantly chose give it one more shot and follow Blake’s lead into analytics until the end of September, after the batch had concluded. We decided that we would lift our heads up at that point to check how everyone wanted to continue. We dipped into our networks one more time and connected with as many BI professionals as we could. We found a gap in tooling to auto-document BI datasets, and launched a VSCode extension to try and fill it. Then the batch finished.

- On 9/22, we came up for air to have that conversation. Nick told the team he was not interested in analytics, and wanted to return to journalism (I saw that coming).

- In the following weeks, various proposals were considered for what should happen next. I did not see myself joining Nick, citing goal/value misalignment, and I refused to break the initial handshake agreement with YC. I did not want to stay the course either, working with Blake in analytics. Blake and Nick were not interested in working together for similar reasons. So my intention was to shudder the company doors and return YC’s remaining investment as a way to preserve our integrity and fail gracefully.

- After deliberating amongst ourselves and consulting the YC partners, we decided to move forward with the dissolution of the corporation and liquidation of assets. This process finished at the end of October, 2023, with the remaining cash being refunded to YC.

Root Cause of Failure

It’s unfortunate we blew up on the tarmac, before takeoff. So what killed that startup?: Goal misalignment. This experience has made me appreciate how you can do everything wrong (check) and you can disagree on almost any subject (check), but if your fundamental motivations for founding a startup are not well-aligned, then your startup is heading for destruction. This happened to us.

Nick’s goal for the business was inextricably attached to his desire to improve the way news is circulated through society and consumed. That was his “why”. My goal, that’s only been strengthened through this ordeal, was to harness the leverage and scale that startups afford to make an impact on the world. I didn’t care about the industry or sector, I just wanted to build a large and successful business. With that objective, there was a natural pull towards opportunities where I have some distinct advantage.

After the decision to join YC, a schism formed in the team fabric, that permeated through every company decision. This rift deepened over time, eventually becoming a chasm, and one that brought down the company.

Fallout

- We owe our journey through pivot hell to this fundamental lack of alignment. We failed to plant ourselves in any one area long enough to get traction. If Nick had to follow a two-step process to achieve his dream, then the first step had to be a quick win. But those are exceedingly rare in startups. Anytime we gained momentum along a vector, we’d surrender as soon as we encountered resistance. But no successful startup has been built without running through walls.

- Although Nick was in the driver’s seat, I was an enabler. Even though I knew that traction is a function of

effort * learning rate * timewith a single customer problem, I failed to convince Nick and Blake to stick when they wanted to quit. - Another symptom I observed: We over-intellectualized the idea selection process. We had complex frameworks for deciding whether a domain was worth committing to or not, which were valid in theory, but in practice, it’s just hard to get any sort of definitive evidence in either direction. You’re faced with an overwhelming amount of conflicting and murky signals, and so you have to summon intuition, empathy, grit, and giving-a-fuck to pick an area you can stick with long enough to find critical business insights.

- Although Nick was in the driver’s seat, I was an enabler. Even though I knew that traction is a function of

- I don’t know if it was the pivot fatigue, or the pressure of demo day, or the perceived progress our YC peers were making, but as soon as we entered a new space, we’d pounce on a problem when we observed even the faintest evidence, instead of being more measured in truly understanding the users and their context. I also attribute this behavior to our lack of emotional connection to the users and their problems.

- On a personal level, the YC-decision was a turning point for Nick. He was struggling to cope with the loss. Nobody died, but you can tell that he was dealing with a deep emotional angst. The team’s strong potential was Nick’s rationale for continuing. Early in the transition, he would repeat that. But at the same time, he was battling with this urge to chase his dream after having given so much of his career to help others achieve theirs.

- I can relate. I like to claim that my motives for pursuing entrepreneurship are pure. I’m driven by the desire to help others and startups are a high-leverage vehicle for manifesting that. That’s not a lie but it hides a complex web of motivations, including autonomy. I’m drawn to the idea of creating my own business from the ground up because I can accomplish that without having to suffer the whims of a boss. Nick clearly shares that desire — He doesn’t want someone imposing constraints on what he can and cannot do — And seeing that reflected helped me acknowledge that part of myself.

- In the final analysis, Nick did not wish to make a concession for a shared vision that we could all own, which honored our personal interests and drivers. That’s fine. But if personal autonomy is a value that’s important to me, it’s an implicit contract I cannot agree to.

- When Nick reached his breaking point in August, my faith in the team’s capacity for success began to attenuate. Without Nick acting as a shim between Blake and myself, our personalities and philosopholies clashed. I was confronted with another jarring realization: In Nick’s absence, Blake and I could not find a sustainable arrangement.

- During my denial phase, subsequently after Nick’s revelation, I was desperate to figure out a way to back the truck for him. I spewed forth loads of ideas with the hope of finding one that got Nick excited. But it was too late. We all fell backwards into Blake’s interest in analytics and BI. This was an example of a counterproductive behavioral pattern. One I have followed since the inception of the company. I would sacrifice my interests and convictions, instead following others, in an effort to keep the team united and moving forward. This was a byproduct of my misplaced faith in the team, and I doubt this could’ve rescued us from our fate, but I wish I was less forgiving, more aggressive about defending my opinions, and willing to put my foot down.

- When looking back, historians will declare this moment as the trigger for the end — the point of no return. We all acquiesced to Blake’s instruction without challenge over the next six weeks. It felt like we were dribbling out the clock. We’d all lost trust in what we were doing and no longer believed in each other.

Our mismatched goals tore the company apart, as we couldn’t settle on a direction. It culminated in Nick yearning to return to journalism, and everybody realizing we had divergent motives.

Lessons Learned

-

The importance of goal alignment. This one’s a no-brainer. If the founders don’t agree on the same overarching ambition for the company, then it introduces friction into every decision that’s unmanageable in the long run. You need to agree on the exit strategy and the vision.

a. Nick had a tight grip around a vision. Which I respect. But it’s not a vision we have in common. His stubbornness of vision traded-off my pragmatism and my goals.

b. The decision to build a startup–given the brutally low odds of success–is irrational. It’s born out of an illogical belief. Nick’s belief lied in the potential to disrupt news media. My campy belief was in the team. At some point during the batch, Nick no longer believed in the team. This was a knife through the heart but I’ve since gotten over it. Thereafter, I also irrevocably lost that belief.

-

The transitive property doesn’t necessarily apply to co-founder compatibility. Nick and I got along (except when it came to the most critical element), Nick and Blake got along, but it turns out Blake and I were a poor match (we didn’t have a pre-existing relationship).

a. Why were we not a good fit? I can articulate some of the rationale and some of it I cannot. It’s a gut feeling. But after the rosy tint wore off my glasses, and I listened to my subconscious, I identified a lot of reasons. So I’ve also learned to trust my gut.

-

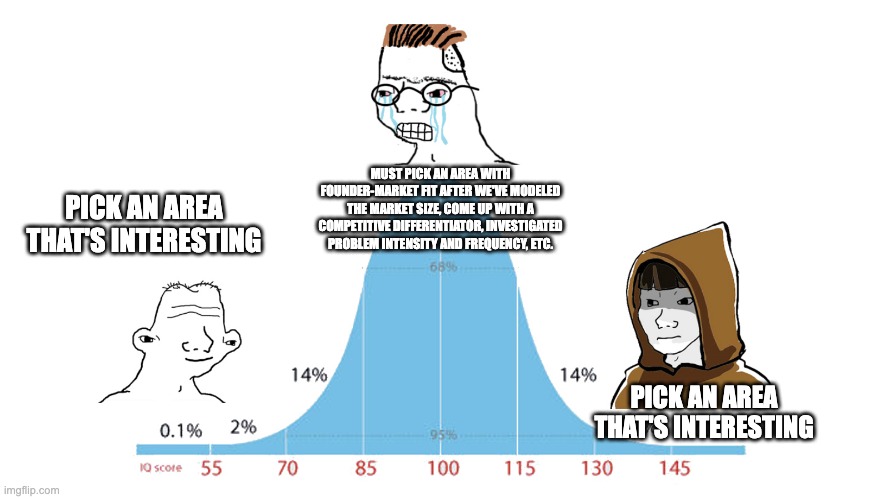

Just pick an area that’s interesting. When it comes to what the market the business operates, I traversed the full length of this mid-wit curve:

The lesson: Just pick something deeply interesting you care about, remain committed long enough, and success will likely follow.

-

Self-sacrificing is a losing strategy. You don’t really score points, at least points that matter, for being self-sacrificing. Kowtowing to the opinions of others for the sake of avoiding team conflict, and hence risking a break-up, is such an idiotic way of keeping the team together. Success keeps the team together. And you do that by challenging people with your ideas, and through the alchemy of high-minded debate, you get winning decisions.

-

You’re never invincible. I thought we were going to crush the startup game. I was wrong. I thought I was above all the typical startup mistakes. I was not. I’m walking away from this crash a lot more humble. And a lot more paranoid.

Conclusion and Acknowledgements

If you’re confused about who to blame at the end of all this, then I wrote this up well. I share the responsibility of this outcome equally with my former co-founders.

Circling back to what I wrote in the introduction: “In hindsight, it was simultaneously the worst decision for the company, but the best decision I’ve ever made.” Deciding to do YC put an early spotlight on the team’s divergent goals and philosophies. If we had chosen the alternative, I probably wouldn’t have encountered this revelation until months or years had passed. So in all honesty, continuing with Factored Media was the greatest thing to never happen to me. It’s like I always tell myself: Success is the best outcome. But failing fast is the second best. So, I’m pretty grateful for how things turned out.

And getting to participate in YC was the ride of a lifetime. I soaked up so much. From lessons to connections.

I did my best to approach this analysis with honesty, humility, and a desire to learn from the failure. I’m grateful to all the people we interviewed, our YC partners, everybody who offered advice along the way, the rockstar founders I met, and of course, for my former co-founders. (Nick and I remain friends to this day.)

With this chapter closed, it’s time to get back on the saddle.