I find myself constantly mulling over this question. Even though it’s impossible to prove or disprove! It’s an important question because it does have subtle implications on how you steer a company. And for those who are wandering space-time for a startup idea, it does affect how selective you are. If you believe that if plenty of unicorns are waiting to be found, you’ll be less picky about the entrypoint.

Since this problem can’t be subject to scientific methods, the best we can do is understand it with a reasonably good mental framework–plus some hand-waving–and see if that is, at least, directionally consistent with the truth.

The Framework

Idea Maze

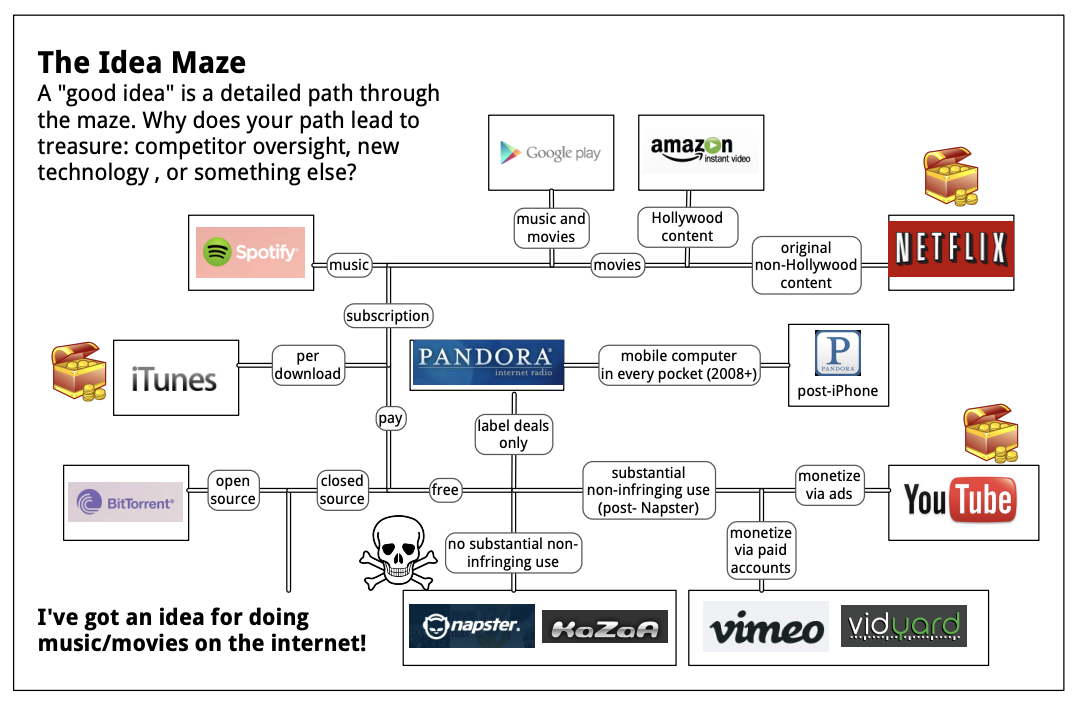

The “idea maze” is a good starting point to build a conceptual framework. It’s an analogy frequently used to describe the complex, multi-year journey a business takes from initial idea to success. The journey is anything but straightforward, and just like a path through a maze, there are a series of twists and turns, some driven by intentional actions and others by external forces. Most of the time, we only see the major turning points in the path taken by one company. We don’t see the paths not taken by that company, and certainly don’t think much about all the dead companies that hit deadends and couldn’t survive long enough to get unstuck. Here’s a sample maze that outlines the different roads many different companies took–some towards death and others to glory–in the Internet music/movie industry:

(source)

A common misconception is that entrepreneurs enter the maze in search of an original and viable idea, and leave the maze once it’s found (you might’ve heard remarks like, “I’m still stuck in the idea maze” from aspiring founders). But idea discovery is just the beginning. The maze encompasses the entire company lifecycle–I would argue–from seedling to mighty oak (or tragic death in most cases). You’re always faced with forks, and there’s always a chance you can take a wrong turn, whether it happens during infancy, during a growth spurt, or following full maturity. Like how Kodak failing to pounce on the rise of digital cameras. Therefore, the aim is to survive, not “exit” the maze.

Idea State Machine

But instead of sticking with the “maze” metaphor to represent these complex decision trees, let’s consider a state machine, composed of states and transitions. I prefer casting the maze to a state machine for a couple of reasons:

- Where a maze is just a planar graph (ie. can be drawn on a plane without criss-crossing edges), generalizing beyond a plane lets us model the extraordinary, but closer-to-reality, level of connectivity between decision points and the many alternatives.

- A state machine is a formal model, amenable to many computer science concepts (some of which I will make reference to), unlike mazes, which don’t have a technical equivalent. But when it’s convenient, I’ll refer back to the maze, because it’s easier to visualize in your head.

The “state” in “state machine”, represents the business as a snapshot in time, just prior to a decision point. In more discrete terms, you can think of “state” as the company’s balance sheet, including an accounting of the assets–hard (eg. personnel) and soft (eg. brand)–liabilities (eg. lines of credit), cap table, etc. This is a reductive view of a company but good enough as a mental model. Lets use \(S\) to denote the space of all possible states.

A decision point marks a point where the company is at a crossroads, deciding whether to open source their IP or remain closed source, or open a new brick-and-mortar store in an untouched region, or partner with an enterprise for distribution, etc. By enacting a decision, the business transitions between states, not all of which are possible. You can’t just leap from a napkin sketch of a business plan to a billion-dollar company. You need to follow a long chain of decisions / state transitions, with the judicious acquisition and allocation of resources to grow the business. The transition function, \(M\), maps a state to a probability distribution over states, or \(M: S \rightarrow \mathcal{P}(S)\) (we’re allowing non-deterministic transitions, because hey, in the world of entrepreneurship, no outcome is definite). The ability for a company to make a transition depends on an assortment of factors, which I’ll detail in the next sub-section.

Agent

As the company traverses from state-to-state, let’s model it as an agent. Much like an agent in a reinforcement learning setting: It’s a decision-maker in an environment (the state space) where it chooses between actions (possible transitions), each producing a reward or penalty, in order to maximize cumulative rewards. The specifics of reinforcement learning aren’t important here, except that each transition yields a reward in the form of positive profit, or incurs a penalty in the form of financial loss.

There’s no guarantee an agent can make a leap from one state to another. It dependes on so many variables. Here’s one way to define the likelihood:

\[p(s', r | s, \alpha, \delta, \sigma, \omega)\]Where,

- \(s'\) is the destination state.

- \(r\) is the expected reward (or loss).

- \(s\) is the current state.

- \(\alpha\) is the business’ effectiveness of execution.

- \(\delta\) is the ability to raise fresh capital.

- \(\sigma\) is the current income, ie. burn rate if the business is in the red or profits if it’s in the black.

- \(\omega\) represents the state of the surrounding world (competitors, markets, technology, etc.) outside the agent.

There’s alot packed into \(\alpha\). Execution includes things like a team’s creativity and resourcefulness, as well as work ethic and organizational culture. For pre-PMF startups, it depends alot on their mastery over the OODA loop, etc. This metric fluctuates over time and can decrease, especially as the organization gets bigger. Over time, a company can rack up “diseconomies of scale”, for example, that arise from tensions between investing in existing products and revenue streams vs. developing new ones.

Ok, enough with the abstractions. Lets examine a concrete example: Suppose your startup has got $1M in the bank and is default dead. You decide you want to build an entertainment and media empire that’s competitive with the likes of, say, Disney. Well, to mount a direct assault, you’re going to need a monster round of financing, otherwise the chances of you delivering on formidable content and stealing signficant market are vanishingly small. Said another way, the probability of that direct state transition is very low–with any reward expectation. But say it’s the 1990s and you opt for a more oblique path. You start by distributing DVD collections via mail delivery–with no due dates and a massive selection. This is a feasible state change and you’re rewarded with a user base, brand recognition, and pocketbook. You then leverage your assets to acquire streaming rights of movie and TV content, and decide to distirbute it over the Internet. Another reasonable state transition that leads to a larger user base, higher-profile brand, and even deeper pockets. Now, as a mature business with loads of ammunition, you can finally move into self-producted programming and achieve your original ambitions. This story might sound familiar. It’s the path Netflix took through the state machine. Aside: This case study reveals a fascinating property of the transition graph: A direct transition from an initial state to a target state may have low probability, but a longer path with multiple transitions may have better odds, even though the final odds are the multiplication of individual transition probabiltiies! (This is the central idea behind path dependency that we’ll touch on some more later.)

Extensions & Implications

Decision-Making

How do successful teams select which turn to make at each state? Based on the crude model we’ve developed so far, you might think that the rational choice in each state is to greedily pick the transition that maximizes the expected return,

\[s', \_ = \text{argmax}_{s', r} r * p(s', r | s, \alpha, \delta, \sigma, \omega)\]However, you can easily come up with counter-examples to invalidate this strategy. For instance, it’s common for venture-backed companies to operate at a financial loss for a long time in order to scale and extinguish competitors. Netflix incurred a large financial deficit when transforming from a DVD rental service to a streaming service, and later when it expanded globally and started producing original content. Those decisions to sacrifice the bottom-line for the top-line were likely crucial in order to reach a stronger market position.

So agents in the state machine don’t only consider immediate transitions, but give some non-zero weight to the potential rewards aggregated over all future possible paths, as defined by this equation:

\[Q(s' | s) = p(s', r | s, \alpha, \delta, \sigma, \omega)(r + \gamma \sum_{s''}Q(s'' | s'))\]Where,

- \(\gamma\) is some discount factor on future rewards.

- \(s''\) represents a state two hops away from \(s\) in the state-transition graph.

(If you’re familiar with reinforcement learning, this is variant of the Q-value function.)

I doubt leaders at a company break down decisions in such explicit terms (how would you even assign values to these variables!?), but it’s an approximation of their reasoning process, which balance short-term and long-term outcomes.

Discount Factor

The discount factor, \(\gamma\) essentially captures how much a company values the short-term vs. the long-term. And it need not be fixed, eg. it can vary based on a team’s disposition towards prioritizing the future over the present or outside circumstances. You see the weakening the discount factor with large industry incumbents who fail to bring innovative products to market because they might cannabalize existing revenue. Many of the fundamental breakthroughs behind ChatGPT were originally authored by Google, but Google suffered from the classic innovator’s dilemma and missed the chance to be first-to-market with an LLM-powered assistant.

Cash Balance

When you unpack a company’s balance sheet (a company’s “state” in our framework), a key component is the cash balance, \(s = \{B, ...\}\). It’s the health bar of the business, and it can withstand damage or it can accrue health points, but if it ever drops to 0, then the business becomes insolvent. This marks the death of the company and it ceases to exist in the state machine. The growth or depletion rate (\(\sigma\)) in cash reserves can heavily influence whether a company is veering towards or away from death. Take WeWork as a cautionary tale. Even though it survived, a period of irresponsible spending in aggressive expansion and extravagant purchases (eg. upscale interior designs, lavish employee perks) contributed to a loss in investor confidence (huge dip in \(\delta\)), and ultimately its failed IPO in 2019. And its struggled ever since.

For early-stage startups, managing cash is so important. Many are probably operating with negative cash flow so they need to strike PMF before the timer runs out. Negative returns are a reflection of an un-workable business model, and can diminish a team’s ability to fundraise (\(\delta\)), thereby reducing optionality in state movements. Escaping this rut means nailing PMF and the best way to do that is by increasing the number of “shots on goal.” The more quality attempts a company can take at hitting PMF, the more likely it will succeed. So the number of hypotheses you can afford to test is a good way to thinking about cash in a pre-PMF startup. A highly-capable team can sustain a high rate of execution (high \(\alpha\)), and iterate through more hypotheses, outpacing burn, until they find PMF.

World

The “world” variable, \(\omega\) belies a vast amount of complexity. It’s meant to encapsulate the state of the environment, so basically the entire universe, in which the company exists. It includes the state of technology, markets, consumer and business behavior, etc. Naturally, it depends on time (\(\omega(t)\)). I consider this to be a weakness in the model. It represents so much information, and in a way that’s impossible to disambiguate into action. Nevertheless, you can’t understate its impact on transition probabilities. The landscape underneath a company is constantly shifting, making some state transitions more likely, and others less so. The rapid adoption of cars was a tailwind for the fast food industry, making it easier for many fast food players to expand their market share. Black swan events like the recent Covid-19 pandemic can eliminate a lot of possibilities for companies in, say carpooling, and open up others for companies in, say remote work.

Startups and Businesses

Most people conflate startups with “technology companies”, but startups are an attempt to build a “huge” business, with at least 100s of millions in revenue (the rule of thumb these days is to apply a 10x multiple on revenue to technology startups). Startups usually taking advantage of cutting-edge technology, but there are physical operations (eg. Starbucks, McDonalds) that have grown fast and reached global scale.

We also often conflate startups with venture capital investments. A startup can theoretically scale with steady organic growth, but more often, it accepts VC money to grow rapidly. The latter can really turbocharge the business but the trade-off is committing to an exponential trajectory. The “rewards” a startup collects as it charts a course through the idea state machine must exhibit geoetric growth,

\[r_1 + r_2 + r_3 + r_4 + ... \in O(c^n)\]So can any company become a unicorn?

In other words, is there always a traverable path from any starting state, \(s_0\), to a unicorn? (The unicorn status is somewhat arbitrary. The question is whether any company can become “huge”.)

It’s totally conjecture, but my belief is that it’s true…under certain conditions:

- The idea state machine is becoming more connected, so more unreachable states can be occupied and more transitions are possible. Put another way, for more \(s', s \in S\),

- The rate at which transitions probabilties are growing is exceeding the rate at which those probabilties are dropping. So,

Let me clarify, I believe any company can become “huge”, but not every company. We live in a universe with finite resources and as entities in an economy, you and I are competing for those resources to put towards activities we deem most valuable.

Under these conditions, a team that rates extremely high on execution (\(\alpha\)), the beachhead is irrelevant. You can build in any direction, as long as the team strictly manages burn, so the company doesn’t die, and rapidly tests the possible branches in each state to identify the promising path (which is nearly guaranteed to exist at some point if those conditions hold true).

HR platforms offer an interesting case study. So many HR-tech startups, from Lattice to Gusto, have demonstrated there are multiple paths to an HR platform. Lattice started with employee performance management. Gusto started with payroll. But with consectuive product extensions and expansion into new product lines, eg. consolidate employee logins, add benefit management, we get an undifferentiated sea of HR SaaS solutions.

In this video, YC partners mention that it’s rare that a startup fully taps their initial market and is unable to acquire new revenue. In a densely-connected state graph, adjacent markets are certain to exist.

How do we know the idea state machine is trending bigger and denser? Here’s my speculative justification: The economy is driven forward by technology and innovation, which emerges from the agents navigating the state machine. Since we obsertve the economy is steadily growing, and the arrow of technology and innovation is accelerating forward, we can infer the state machine, as a whole, must be expanding as well. This question really needs its own treatise (authored by economic scholars), but here’s a shoddy attempt at describing the underlying dynamic: Technological inventions, a new solution to a problem, fuels innovation, tieing solutions to problems to generate value. Innovation gives rise to increased specialization (eg. the introduction of cars created demand for specialized companies to produce asphalt for roads). Increased specialization gives way to increased trade, which means the overall economy can grow bigger (eg. two companies can do better in aggregate if one focused on designing and manufacturing cars and the other focused on paving roads). The bigger the economy, the easier to develop new technologies, innovations, and specializations, since so many specializations depend on economies of scale to work. And the flywheel continues.

Path Dependence

…

Theory and Practice

How do we reconcile the paradox between this theoretical argument and the observation that proportionally, so few companies ever become unicorns?

As I mentioned earlier, limitation on economic resources plays a role. But our existing vehicles for financing startups impose expectations that limit how much of the state machine can be explored. Institutional VC’s typically have a decade-long investment horizon for many of their funds, and so a startup is limited to those state transitions that allow it to grow exponentially to a billion dollar valuation in that timeframe, which frankly, may not always exist. That necessitates a growth rate of ~6x (which is what you get when you solve for \(x\) in \(100000000 = x^{10}\)). Even inside of the complex and vibrant state machine underpinning our economy, such exponential growth curves are rare. That’s why the many breakout successes we’ve seen in recent decades occurred on the back of gigantic waves. Startups like Airbnb and Dropbox were able to find and attach themselves to a single high-growth S-curve, and exploit it fully. But as a founder, you’re not limited to a single S-curve. Other companies, like OpenAI, took a more squiggly route through the state machine, continually launching new products and finding smaller S-curves that they can stack together to exceed the billion-dollar market cap.

Outside of venture financing, you can find examples of companies that took their time navigating the state machine. Nintendo began as a playing card company in the late 19th century and slowly evolved through various industries including toys and eventually, video games. Their journey through the state machine reflects a series of iterative transitions, each building upon the last, and still exponential in nature. However, unlike startups following the venture-backed, rapid-growth model, Nintendo’s path allowed for gradual exploration and adaptation over decades.

Nevertheless, I believe there’s an ample supply of exponential growth curves lurking in the state machine, reachable from nearly any state. Its the natural tendency of a system with gemoetric compounding complexity. Decades ago, being a millionaire was like being a billionaire today (even on an inflation-adjusted basis). But today, millionaires exist in abundance. So there’s an infinite amount of unicorn potential out there, but the reason so few startups fulfill that potential is partially due to constraints imposed by financing, but also due to poor execution and bad decision-making.

Locus of Control

Shifting the locus of control to founders is a subtle theme you may have noticed. The environment around a business is inherently over-powering, and there’s very little influence even large corporations can exert. But I believe founders have more control over the destiny of their company then many realize. If the state machine is adding more edges, and more of them are becoming viable, then attaining success is simply a matter of choosing the right path and crossing it. That’s within the control of founders. So although execution isn’t “everything”, its role in today’s idea maze has never been greater.

Conclusion

I know what you’re thinking, so what? This might be interesting philosophically, but what purpose does it serve founders and operators? I believe the extent to which we understand the chaos of startups, we can have some control over it, and increase our odds of success. The more clearly we can articulate what we’re trying to do and the world we operate in, we gain clarity towards how we should function to accomplish our goals. Having this mental framework brings me some peace of mind as I wander the ambiguity.

Disclaimer: I’m a proto-founder, and I’ve never seen or been part of the full startup movie from the inside–beginning to end. So these musings come are derived from some lived experience, but also my ongoing study of business history.

If you have any counter-arguments or suggestions, send them my way. I’m always looking for ways to improve my mental models.